UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines

UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines: A Cultural and Natural Tapestry

The Philippines, an archipelagic nation in Southeast Asia, is renowned for its breathtaking landscapes and rich cultural history. Among its treasures are six designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites, a mix of cultural and natural wonders that reveal the country’s unique heritage. These sites include three cultural sites and three natural sites, although two of the cultural designations encompass multiple locations. Of the natural sites, one is so isolated that it is only accessible to divers, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the world beneath the waves.

So let’s now delve into the significance of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines, highlighting the cultural importance of four historic churches and five clusters of rice terraces, as well as the extraordinary biodiversity and geological wonders that make the natural sites so remarkable.

1. The Cultural Treasures of the Philippines

The Philippines’ cultural heritage sites reflect the country’s vibrant history, shaped by indigenous traditions, colonial influences, and the evolution of local communities. Three of these sites have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, two of which are grouped as collective representations of the country’s cultural landscape.

1.1 Baroque Churches of the Philippines

The Baroque Churches of the Philippines are a testament to the blending of European architectural styles with local building techniques and materials. This collective site comprises four churches, which together showcase the influence of the Spanish colonial period from the 16th to the 18th centuries. The UNESCO designation includes the following churches:

These four churches collectively represent the fusion of European and Filipino influences in architecture and religious expression. Their UNESCO inscription in 1993 highlights the cultural importance of these structures, not only as places of worship but as symbols of resilience and adaptation in the face of natural disasters and colonial pressures.

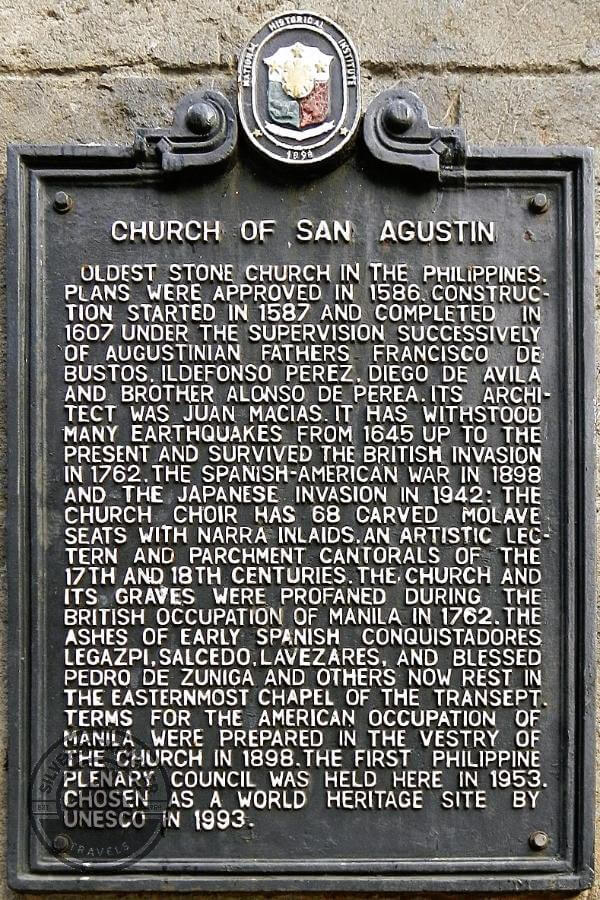

San Agustin Church, Manila

San Agustín Church is a Roman Catholic church under the auspices of The Order of St. Augustine, located inside the historic walled city of Intramuros in Manila. Completed by 1607, it is the oldest church currently standing in the Philippines. No other surviving building in the Philippines has been claimed to pre-date San Agustin Church.

In 1993, San Agustin Church was one of four Philippine churches constructed during the Spanish colonial period designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, under the classification “Baroque Churches of the Philippines”. It had been named a National Historical Landmark by the Philippine government in 1976.

The present structure is actually the third Augustinian church erected on the site. The first San Agustin Church was the first religious structure constructed by the Spaniards on the island of Luzon. Made of bamboo and nipa, it was completed in 1571, but destroyed by fire in December, 1574 during the attempted invasion of Manila by the forces of Limahong. A second church made of wood was constructed on the site. This was destroyed in February, 1583, in a fire that started when a candle set ablaze the drapes of the funeral bier during the interment of the Spanish Governor-General Gonzalo Ronquillo de Peñalosa.

The Augustinians decided to rebuild the church using stone, and to construct an adjacent monastery. Construction began in 1586, from the design of Juan Macias. The structure was built using hewn adobe stones quarried from Meycauayan, Binangonan and San Mateo, Rizal. The work proceeded slowly due to the lack of funds and materials, as well as the relative scarcity of stone artisans. The monastery was operational by 1604, and the church was formally declared as completed on January 19, 1607, and named St. Paul of Manila. Macias, who had died before the completion of the church, was officially acknowledged by the Augustinians as the builder of the edifice.

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during World War II, San Agustin Church was turned into a concentration camp for prisoners. During the final days of the Battle of Manila, hundreds of Intramuros residents and clergy were held hostage in the church by Japanese soldiers; many of the hostages would be killed during the three-week long battle. The church itself survived the bombardment of Intramuros by American and Filipino forces with only its roof destroyed, the only one of the seven churches in the walled city to remain standing.The adjacent monastery however was totally destroyed, and would be rebuilt in the 1970s as a museum under the design of architect Angel Nakpil.

San Agustín Church measures 67.15 metres long and 24.93 metres wide. Its elliptical foundation has allowed it to withstand the numerous earthquakes that have destroyed many other Manila churches. It is said that the design was derived from Augustinian churches built in Mexico,and is almost an exact copy of Puebla Cathedral in Puebla, Mexico. The facade is unassuming and even criticised as “lacking grace and charm”, but it has notable baroque touches, especially the ornate carvings on its wooden doors.The church courtyard is graced by several granite sculptures of lions, which had been gifted by Chinese converts to Catholicism.

The church interior is in the form of a Latin cross. The church has 14 side chapels and a trompe-l’oeil ceiling painted in 1875 by Italian artists Cesare Alberoni and Giovanni Dibella. Up in the choir loft are hand-carved 17th-century seats of molave, a beautiful tropical hardwood. The church contains the tomb of Spanish conquistadors Miguel López de Legazpi, Juan de Salcedo and Martín de Goiti, as well as several early Spanish Governors-General and archbishops. Their bones are buried in a communal vault near the main altar. The painter Juan Luna, and the statesmen Pedro A. Paterno and Trinidad Pardo de Tavera are among the hundreds of laypersons whose remains are also housed within the church.

San Agustin Church also hosts an image of Our Lady of Consolation (Nuestra Senora de Consolacion y Correa), which was canonically crowned by Manila Archbishop Cardinal Jaime Sin in 2000.

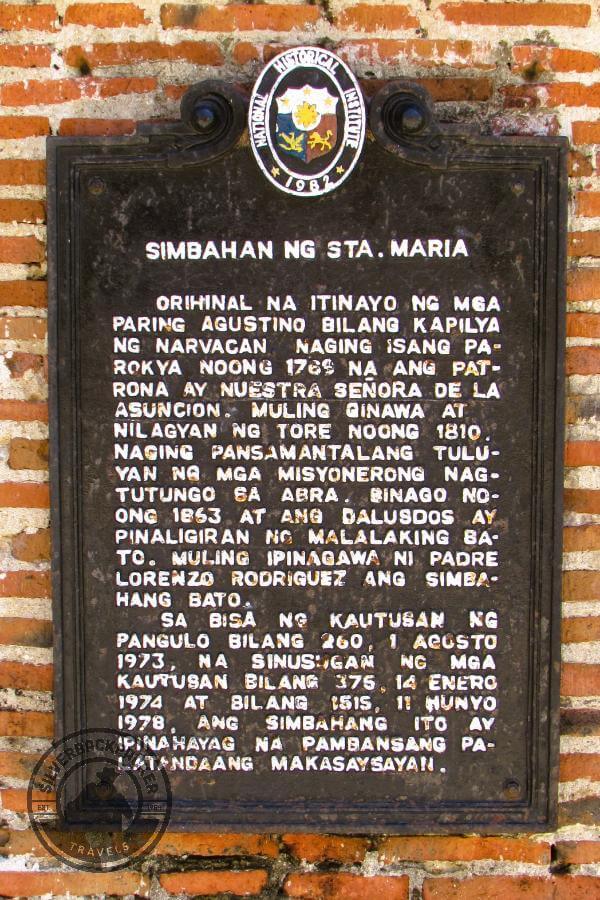

Church of Nuestra Señora de la Asuncion, Santa Maria (Ilocos Sur)

Santa Maria Church is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that sits on top of a 60-foot hill in Santa Maria, a town in Ilocos Sur. From the top, you get an amazing view of the surrounding plains. The church itself is 100 metres long and 23 metres wide, with an impressive 85-foot staircase made from granite. It’s surrounded by thick, fortress-like walls that are reinforced every 10 metres with stone supports, making it look like a citadel. Santa Maria Church is located 38 kilometres from Vigan City and 370 kilometres from Metro Manila. If you’re coming from La Union, it’s about a two-hour drive.

The church was originally built in 1765 by Augustinian friars during the Spanish colonial period as a chapel in Narvacan. It became a parish church in 1769, dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Asuncion. In 1810, the church was rebuilt, and a separate bell tower was added. Over the years, it also served as a resting place for priests travelling to Abra. In 1863, the church was fortified with large stone walls for protection, and Father Lorenzo Rodriguez led its remodeling.

Santa Maria Church was declared a national historic landmark in the 1970s, with a marker placed by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines. In 1993, it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site as one of four Spanish earthquake Baroque churches in the Philippines. By 2015, it was also declared a National Cultural Treasure. Today, it’s a popular tourist spot in Ilocos Sur, drawing visitors to admire its history and stunning architecture.

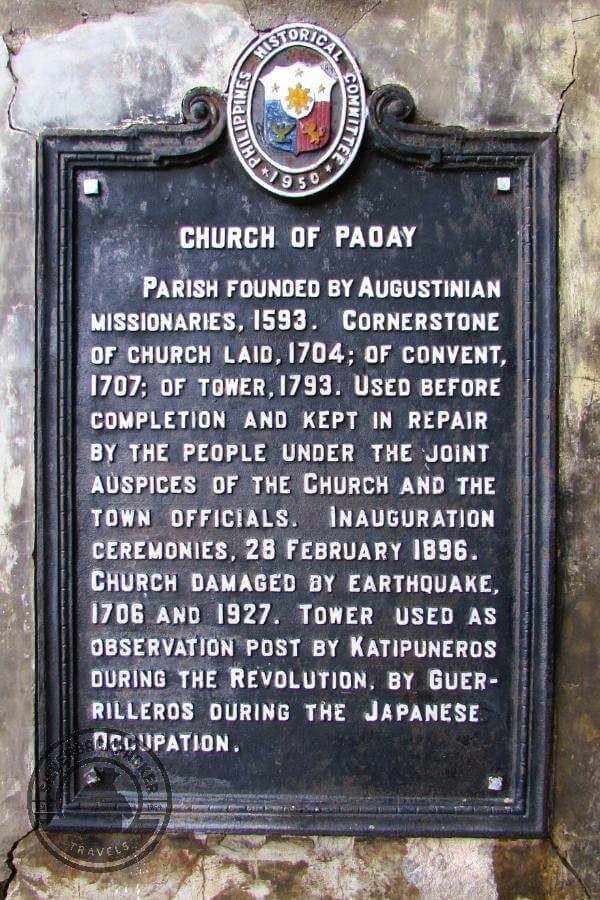

St. Augustine Church, Paoay (Ilocos Norte)

One of the most iconic of the Baroque churches, Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte is known for its massive buttresses, which provide structural stability against earthquakes. Built in 1710, the church is constructed primarily from coral stones and bricks. The bell tower, separate from the main church building, was historically used as a lookout point for approaching threats.

St. Augustine Church, known as the “Earthquake Baroque” church, is a fantastic example of a unique architectural style that blends European Baroque with the Philippines’ need to withstand earthquakes. Since destructive earthquakes have often damaged churches across the country, this design adapts to those challenges. You can also see influences from Javanese architecture, reminiscent of the famous Borobudur temple in Java.

In his book, Fr. Pedro Galende highlights how the church’s massive structure is balanced with elegance and fluidity. The church features a pyramidal design typical of the Baroque style, with details inspired by the seal of Saint Augustine, the Spanish royal emblem, the Pope’s logo, the sun god “init-tao,” and stylised clouds from Chinese art.

Nearby, a three-storey coral stone bell tower stands proud. This tower was used as a lookout in 1896 by the Katipuneros during the Philippine Revolution against Spanish rule, and later by Filipino guerillas during World War II.

Historians note that the bell tower was also a symbol of status for the local community. When a prominent family held a wedding, the bell would ring more loudly and for longer than for a less wealthy couple’s wedding.

In 1993, St. Augustine Church was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated as one of the finest examples of Baroque churches in the Philippines. Its striking architecture is marked by huge buttresses on the sides and back.

The church has faced damage from earthquakes, particularly in 1865 and 1885. In 2000, during excavations inside, a prehistoric human skeleton and fragments of pottery were found, which are now displayed at the National Museum. Former President Ferdinand Marcos even declared Paoay Church a national treasure.

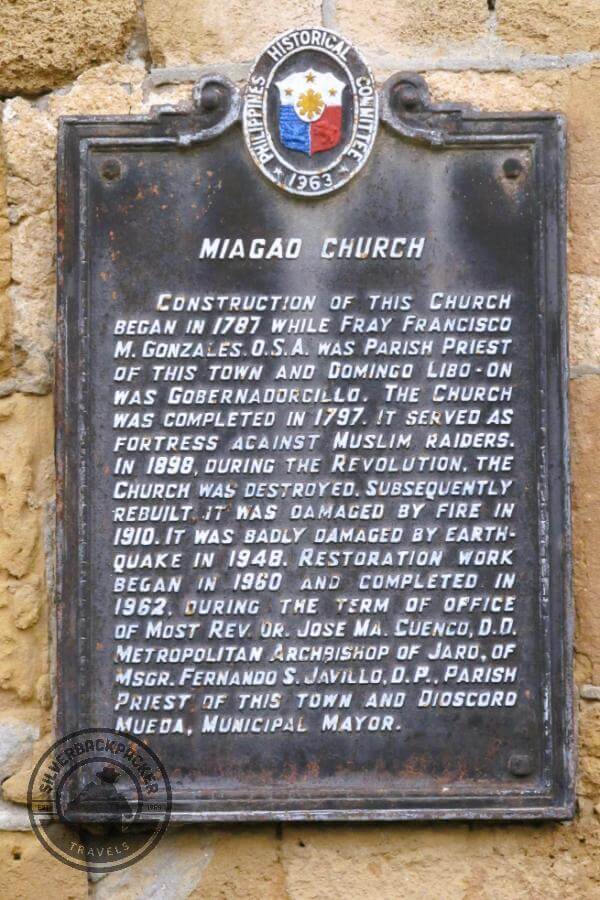

Santo Tomás de Villanueva Parish Church, Miagao

The best time to see Miagao Church is at sunrise. At the first break of daylight, a thin pale yellow light creeps up, gradually turning golden and blossoming into an orange blush as the sun streams full force. Breathtaking.

Sandstone does that, being quartz aggregate with silica and calcium carbonate, the colour variations are dictated by mineral inclusions, iron oxide giving the various pinks and reds while manganese imparts the purple tints. The quartz crystals of course, do the magic, making the whole composition glow when light hits the stone blocks.

A series of military and ecclesiastical constructions were created by the Spanish administration in Oton and later at La Villa de Arevalo, covering the area all the way to present day San Joaquin and Miagao in the 17th Century. They were developed to protect the boat building projects and weaving centres along the Southern Panay coastline for the Spice Islands expeditions. Towns along the southern Panay coast supplied timber for ship building, abaca hemp cordage, weavers for sail cloth, iron foundry workers, skilled seamen and ship builders.

The Castile War between Spain and Brunei Darussalam started in 1578. After the sack of Brunei, in a bid for colonial expansionism and a chunk of the spice trade, Spanish possessions in the Visayan Sea area were subjected to frequent retaliatory attacks. Many of these coastal villages built watchtowers and church fortresses to protect and temporarily house the populace according to the Laws of the Indies (Royal Decree 111 of 1573). Miagao Church is perhaps the best example of these fortress churches in the Southern Panay coast.

Stone blocks

According to an article written by University of the Philippines in the Visayas Professors Randy Madrid and Jorge Ebay for The Miagao Church Bicentennial Yearbook, 1797-1997, the stone blocks were quarried from the mountains of the nearby San Joaquin towns of Sitio Tubog and Igbaras. This was the third church built in Miagao. Construction started in 1786.

Since the first two churches built on lower ground were susceptible to plunder and pillage, the third church, finished in 1797 after 11 years of construction, was high up on the promontory facing the mouth of the Miagao River.

Thirty-three years later, a fourth story was added to the left tower disrupting the symmetrical balance, but a necessary compromise for seaward watch.

The church foundation extends six metres into the ground. The one and a half metre-thick walls buttressed by four and a half metre-base supports hold the church side walls and bastion towers.

Earthquake Baroque architecture

The fortress church of Miagao is a fine example of Earthquake Baroque architecture, which developed in Portugal (Pombaline architecture in Lisbon), Italy (Sicilian Baroque), South America (San Pedro de las Huertas in Guatemala) and the Philippines, when these places suffered earthquakes in the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Baroque architecture itself began in late 16th Century Italy taking off from the Classical Roman Humanism of the Renaissance, and used its vocabulary in a new rhetorical and theatrical fashion. Unlike Renaissance architecture that is a blend of religious and secular influences, Baroque architecture developed as an expression of the Church’s Counter Reformation propaganda in response to Protestant Reformation.

Using various shapes, light and shadow with dramatic intensity (chiaroscuro), Baroque architecture appealed to the emotions and at the same time was a visual statement of the power and influence of the Church. This style manifested itself in the religious orders like the Jesuits who aimed to encourage religious devotion with the assistance of a pictorial narrative.

In Spain, the Catalan Churriguera family in Madrid, who specialised in retablos and altars, promoted an intricate and almost unpredictable style of ornamentation known as Churrigueresque style Baroque architecture. This style had a profound effect on ecclesiastical architecture in the Spanish colonies. Focusing on florid ornamentation, the Churrigueresque style is a play of architectural elements with no relationship to form and function: none of these elements are structurally supportive.

Saint Christopher

This style is best exemplified in Miagao Church where the main facade is clipped on both ends by two bastion towers, freeing the flat space for focused ornamentation. The main doorway’s elaborate sculptural surround creates an exterior altar that makes the interior altar almost redundant, with its architectural relief of undulating cornices, scrolled shells, attached columns, balustrade and volutes.

The pièce de résistance, however, is the pediment supported by all these elements. Central to the composition is a palm tree with its crown of fronds splayed to fill out the apical half of the triangle. The pediment base runs a course of flora and Saint Christopher with the Infant Christ on his shoulder. Legend says that the saint lived beside a stream where many had drowned and decided to be a porter and help those who cross it. One day, he carries a small child across the stream but the child’s weight nearly crushes him. When they get to the opposite side of the stream, the child reveals himself as Christ, so heavy because he is carrying the weight of the world. Henceforth, the saint was known as Christopher or the Christbearer.

The martyr’s image with the Christ child holding the palm tree is a symbol of missionary activity, which the martyr saint encouraged.

Interestingly, all tropical flora are of New World provenance, with papayas and guavas predominating. Directly below this tableau is a six-lobed and volute niche containing the figures of Saint Thomas of Villanova and two mendicants. An Augustinian friar, writer, preacher and ascetic, St. Thomas was responsible for sending the first Augustinian missions to the

New World.

Papal coat of arms

The ground story level features the statues of St. Henry on the left and the pope on the right niches flanking the main door. The last of the Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian Dynasty, St. Henry was the only member of German royalty to be canonised. The popes’ identity however, is up for debate as the pope’s coat of arms was altered in one of the church renovations: in place of the original, the coat of arms of John XXIII (1958 to 1963) was installed in the 1959 renovation.

The pope at the time of the original church construction was Pope Pius VI (1775-1799). Born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, Pope Pius VI was accused of corruption and immorality and removed from office by the invading French Republican troops under Napoleon Bonaparte. There are no clear pictures of the original papal coat of arms on the façade, but Pope Pius VI’s controversial 24-year long reign (1775-1799) suggests a possible cause for ecclesiastical revision. The whole assemblage is figuratively tied together with clerical tassel and passementerie that somehow lighten the otherwise squat and solid construction.

Sadly, all niche figures are facsimiles of the original, one of which is the figure of St. Thomas that now rests just beneath the choir loft in a glass case to the right of the church entrance. In 2010, Miagao Church underwent cleaning and repair, with the National Museum’s supervision. Broken stone blocks were removed and replaced with matching blocks from the original quarry.

Despite the periodic interventions of war, weather and human folly, Miagao Church today still stands as a fine example of hybrid ecclesiastical architecture guided by the friar’s religious narrative illustration and memory, as well as Filipino-Chinese craft and skill.

Miagao Church by Eugene Jamerlan

(This article was first published in BluPrint magazine in 2011.

1.2 Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras

The second UNESCO cultural heritage site in the Philippines encompasses five clusters of rice terraces in the northern region of the Cordilleras. These terraces, which have been in use for over 2,000 years, are a marvel of engineering and agricultural sustainability. The five clusters are located in the provinces of Ifugao and Mountain Province, each with its own unique characteristics:

- Batad Rice Terraces

- Banaue Rice Terraces

- Mayoyao Rice Terraces

- Hapao Rice Terraces

- Kiangan Rice Terraces

The rice terraces are a testament to the indigenous Ifugao people’s ingenuity and deep connection to their environment. Carved into the steep mountainsides, the terraces create a cascading effect that maximises arable land in a region with limited flat terrain. Irrigation systems, drawn from mountain springs, have been carefully managed for centuries, ensuring the fertility of the land.

In addition to their agricultural importance, the rice terraces hold immense cultural significance. The Ifugao people regard the terraces as sacred, passed down through generations as both a livelihood and a spiritual legacy. The UNESCO inscription in 1995 recognises the terraces not only for their remarkable design and functionality but also for the cultural traditions and rituals that are intricately tied to their cultivation and preservation.

However, the rice terraces face challenges in the modern era, including depopulation, modernisation, and the effects of climate change. Efforts are underway to revitalise traditional farming practices and encourage sustainable tourism, which can help preserve this cultural landscape for future generations.

2. Natural Wonders UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines

Beyond its cultural heritage, the Philippines boasts extraordinary biodiversity and unique geological features that have earned three of its sites a place on the UNESCO World Heritage list. These natural sites reflect the country’s ecological richness, but one of them is so remote that it is only accessible to divers, offering a hidden world of underwater splendour.

2.1 Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park

Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, located in the Sulu Sea, is one of the most isolated and pristine marine environments in the world. Spanning over 97,000 hectares, the park encompasses two atolls and a vast coral reef system teeming with marine life. The reef is a critical habitat for more than 600 species of fish, 360 species of coral, and a variety of sharks, rays, and marine turtles.

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, Tubbataha is globally recognised for its biodiversity and its role as a breeding ground for marine species. The park is only accessible by boat during the diving season, which runs from March to June, and it is a haven for divers seeking to explore its underwater wonders. Due to its remote location, it remains relatively untouched by human activity, ensuring the preservation of its delicate ecosystem.

The importance of Tubbataha extends beyond its beauty; it plays a critical role in the health of the larger marine environment in the Coral Triangle, an area known for its high concentration of marine biodiversity. Conservation efforts, including strict protection measures and limited access, are in place to ensure that this marine park remains a sanctuary for future generations.

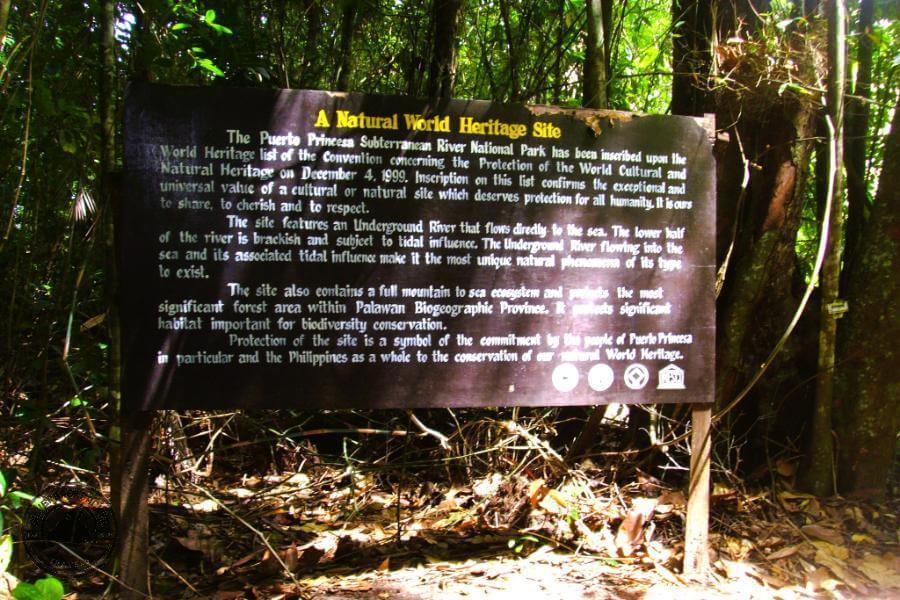

2.2 Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park

The Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park, located on the island of Palawan, is one of the most awe-inspiring natural sites in the Philippines. The park’s most famous feature is its underground river, which stretches for 8.2 kilometres and flows directly into the sea. The river winds through a series of limestone caves, some of which are adorned with stunning stalactites and stalagmites.

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, the park is renowned not only for its geological formations but also for its biodiversity. The surrounding karst landscape is home to a variety of wildlife, including birds, bats, and reptiles. The combination of dramatic cave systems, lush forests, and marine ecosystems makes Puerto-Princesa a remarkable example of the Philippines’ natural diversity.

Visitors to the park can explore the underground river by boat, marveling at the grandeur of the cave systems and the surreal beauty of the subterranean world. Efforts to preserve the park’s natural environment are ongoing, with a focus on sustainable tourism and the protection of endemic species.

2.3 Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary

The Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, located in Davao Oriental on the island of Mindanao, is the newest addition to the Philippines’ UNESCO World Heritage list, having been inscribed in 2014. This mountain range is known for its diverse ecosystems, which range from lowland forests to montane and mossy forests at higher elevations.

Mount Hamiguitan is home to a wide variety of flora and fauna, many of which are endemic to the area. The most famous of these is the Philippine eagle, one of the largest and rarest eagles in the world. The mountain’s rich biodiversity also includes several species of pitcher plants and orchids, making it a hotspot for plant life.

The inscription of Mount Hamiguitan as a UNESCO World Heritage Site highlights its importance as a biodiversity hotspot and a sanctuary for endangered species. However, the mountain is also vulnerable to threats such as illegal logging, mining, and habitat degradation. Conservation efforts are focused on protecting its ecosystems and ensuring the survival of its unique species.

The Historic City of Vigan, Ilocos Sur

Vigan is a really special place in Asia, known for being a perfectly preserved example of a Spanish colonial town from the 16th century. Imagine a town where the styles from different cultures blend together—like the influences from the Philippines, China, Europe, and Mexico—all creating a one-of-a-kind atmosphere that you won’t find anywhere else in East and South-East Asia.

Located at the delta of the Abra River, Vigan used to be an important trading spot before the colonial times. It sits on the northwestern coast of Luzon, in the Province of Ilocos Sur, which is part of the Philippines. As you walk through Vigan, you’ll see beautiful old buildings and charming streets, making it feel like you’ve stepped back in time. It’s a place where history comes alive, and it’s perfect for exploring and learning about the unique mix of cultures that shaped it!

3. The Challenges and Opportunities of Preservation

The UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines are not only places of immense natural beauty and cultural importance but also fragile environments that require careful management. Both the cultural and natural sites face a range of challenges, from urbanisation and tourism to climate change and environmental degradation.

For the Baroque Churches and the Rice Terraces, preserving the traditional methods of construction and farming is critical. Local communities play a vital role in these efforts, as their knowledge and practices are key to maintaining the integrity of the sites. Sustainable tourism initiatives are also being developed to provide economic benefits to the communities while minimising the impact on the environment and the cultural landscape.

In the case of the natural sites, particularly Tubbataha Reefs, strict conservation measures are necessary to protect the delicate ecosystems. The remoteness of Tubbataha has so far helped to shield it from the more severe impacts of human activity, but as interest in marine tourism grows, careful regulation will be essential to ensure that the reef system remains healthy.

The Philippines’ UNESCO World Heritage Sites offer a glimpse into the country’s rich cultural heritage and incredible natural diversity. From the enduring beauty of the Baroque Churches and the ancient rice terraces to the awe-inspiring underwater world of Tubbataha Reefs, these sites represent the resilience and creativity of the Filipino people and the astounding variety of life found in the archipelago.

However, with such treasures comes great responsibility. The preservation of these sites requires the concerted effort of local communities, government agencies, and international organisations. Through sustainable practices and active conservation, these UNESCO World Heritage Sites can continue to inspire future generations, offering a window into the past while safeguarding the natural and cultural wealth of the Philippines.

Essential Travel Guides

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

of the Philippines

Check Out These Related Posts

Historical Markers of Antique , Philippines

If you enjoyed reading “UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Philippines ” then please share this page with your friends.

Leave a comment below to let me know what you liked best.

Follow Silverbackpacker on Facebook, Instagram ,Twitter and Pinterest for more travel adventures and be notified about my latest posts and updates!

Thankyou for sharing 🙂

Please Note – All blog post photos on Silverbackbacker.com are of a lower quality to enable faster loading and save you data. If you would like to buy or license higher quality copies of any of the photographs you can email us at silverbackpackertravels@gmail.com

All photographs and content on this website remain the property of Silverbackpacker.com. Images may not be downloaded, copied, reproduced or used in any way without prior written consent.

Print purchases entitle the purchaser to the ownership of the image but not to the copyrights of the image which still remain with Silverbackpacker.com even after purchase.

Follow Silverbackpacker for more of his Travels

Facebook @silverbackpacker | Instagram @silverbackpacker

Twitter @silverbackpaker | Pinterest @silverbackpaker

Audere Est Facere – Silverbackpacker.com – To Dare is To Do

Affiliate Disclaimer: Links on this website may be affiliate links that could result in us receiving compensation when you purchase a product or service from that link. You do not pay any extra fees for these items. This helps us to keep this website going. Thank you for your support.

Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Cookie Statement © All Rights Reserved